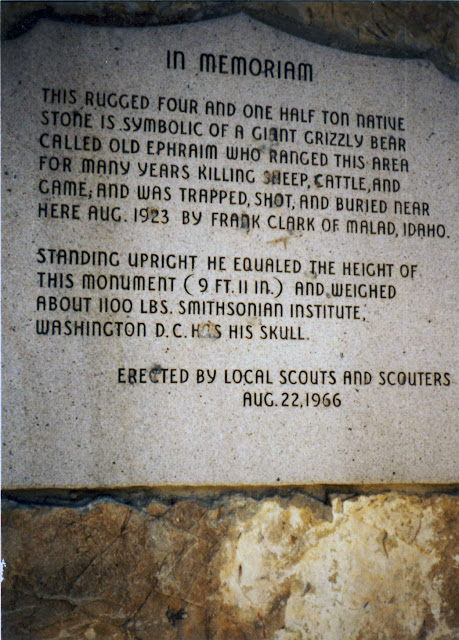

The monument, near Old Eph's final stand, complete with a plaque.

By Lynn Arave

Features and landmarks in mountainous northern Utah weren't graced with the sobriquet "Bear" (Bear Lake, Bear River, Bear Spring, Bear Hollow, Bear Canyon, etc.) simply because the carnivore's name sounded impressive. This used to be prime bear country. In fact, some sheepherders in the 1920s called the Cache National Forest area the "worst-infested bear range in Utah."

Features and landmarks in mountainous northern Utah weren't graced with the sobriquet "Bear" (Bear Lake, Bear River, Bear Spring, Bear Hollow, Bear Canyon, etc.) simply because the carnivore's name sounded impressive. This used to be prime bear country. In fact, some sheepherders in the 1920s called the Cache National Forest area the "worst-infested bear range in Utah."

Most were black bears, but one, a huge grizzly named Old Ephraim, was one of the biggest the world has ever known, and he used to claim a relatively unpopulated area in Cache County as his home.

Although there are probably at best only a handful of black bears left in the Cache National Forest today (and no known grizzlies), the most impressive example of the area's past can be remembered during a visit to a secluded granite monument that marks the general location where this gigantic Utah legend was killed on Aug. 22, 1923.

Although there are probably at best only a handful of black bears left in the Cache National Forest today (and no known grizzlies), the most impressive example of the area's past can be remembered during a visit to a secluded granite monument that marks the general location where this gigantic Utah legend was killed on Aug. 22, 1923.

Featuring two plaques, a monument to the bear was placed there on Aug. 22, 1966, by Cache County Boy Scouts with the help of monument builder Nephi J. Bott and Old Ephraim writer/storyteller Newell J. Crookston. Discounting the base, the stone monument stands 9 feet 11 inches and weighs 1,100 pounds - equaling Old Ephraim's estimated height on hind legs and his weight.

The world's largest wild bear ever is believed to have been a Kodiak brown killed in Alaska in 1894. He weighed in at 1,656 pounds and was 9 feet long. So, since grizzlies average 800 pounds and about 8 feet long, Ephraim was an especially gigantic example of his species.

Actually, it is a miracle in itself that the monument remembering Ephraim ever got to where it is today. The truck that hauled it up the rugged road to its resting place got two flat tires; the hoisting chain later broke and injured one person. Some said this could have been the work of Ephraim's ghost. . . .

Before the monument, today circled by a tidy log fence, was placed there, only a rustic sign and a pile of rocks marked the bear's final resting place.

Frank Clark, a Malad, Idaho, sheepherder, killed Old Ephraim in defense of the many sheep the bear had killed in a decade.

As the legend of Utah's late gigantic grizzly spread, the Smithsonian offered a $25 reward for the bear's skull as proof that it was indeed a grizzly. Local Cache County Boy Scouts of Troop 5, led by their scoutmaster, Dr.George R. Hill, took up the challenge.

They obtained a map from Clark and were able to find the gravesite, dug through what was described as "a stinking mess," found the huge skull and sent it to the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., for verification. The Smithsonian confirmed the size of the huge grizzly. The Scout troop earned the $25, and some Scouts even kept other bones as souvenirs, but none of their whereabouts are known today.

About 54 years later, in 1976, Utah Scouts visiting the Smithsonian were unable to find Ephraim's skull on display. It was later found locked away in a basement storage, and it took the political clout of Sen. Orrin Hatch to convince the Smithsonian to loan the famed skull to Utah State University on a renewing year-to-year basis.

The skull is now on display in the special collections archives on the main floor of USU's Merrill Library (although a plaque on the monument still says it's in Washington).

However, the skull is far from complete and may lack the grandeur you'd expect from such a large bear, which may explain why there have been few, if any, photos ever published of it.

However, the skull is far from complete and may lack the grandeur you'd expect from such a large bear, which may explain why there have been few, if any, photos ever published of it.

Finding the bear's grave

Today a visit to Old Ephraim's grave seems to raise more questions than it answers. A look around the quiet terrain full of quaking aspen and pines may make you wonder what it would have been like to have met the grizzly in his home territory.

Also, since the monument is only near where he was killed, where's the exact spot Old Ephraim died? Finally, why weren't his hide and complete skeleton saved for posterity's sake?

Also, since the monument is only near where he was killed, where's the exact spot Old Ephraim died? Finally, why weren't his hide and complete skeleton saved for posterity's sake?

The bear's killing may seem sad to us today, but I would have been as out of place riding through this area on my mountain bicycle in Eph's time as he would have been if he'd have lived today.

The bear at Ogden's Prairie Schooner Restaurant.

Times were simply a lot different when Old Ephraim was killed. Hogle Zoo wasn't even around in a limited form back then . . . there was no paved road through Logan Canyon . . . the mountains were still a wilderness where survival of the fittest ruled . . . and the death of Ephraim so saddened Frank Clark himself that he vowed never to kill another bear after that.

Times were simply a lot different when Old Ephraim was killed. Hogle Zoo wasn't even around in a limited form back then . . . there was no paved road through Logan Canyon . . . the mountains were still a wilderness where survival of the fittest ruled . . . and the death of Ephraim so saddened Frank Clark himself that he vowed never to kill another bear after that.

Today you rarely see wild bears anywhere. Even in Yellowstone National Park, the bears have retreated or been removed to the wilds. Ephraim was Utah's last known grizzly, and his death perhaps signaled the end of the frontier wilderness in Utah.

Old Ephraim's legend is summarized well by Nephi J. Bott's poem, inscribed at the bottom of the monument:

"Old Ephraim, Old Ephraim, your deeds were so wrong yet we build you this marker and sing you this song. To the king of the forest so mighty and tall, we salute you, Old Ephraim the king of them all."

HOW TO GET THERE: There are four basic ways to reach Ephraim's grave. Automobiles are not recommended for travel on any of the routes.

1. Temple Fork (Forest Service road No. 007). Perhaps the best route (and the one I took via mountain bicycle) is to go on this dirt road, 15 miles up Logan Canyon. From there, it's 2.5 miles of good gravel to Mudflat. After that, the road gets extremely steep and rugged. Take the first right fork in the road and just follow the signs from there. The road starts at 5,797 feet and climbs to 7,430 before dropping down to Ephraim's grave, 6,800 feet above sea level, in the last 2.5 miles.

2. Right Fork (Forest Service No. 047). This road junction is located just nine miles up Logan Canyon. The first mile is paved to a girls camp and to Lodge Campground. Then the dirt road is rather rugged, and it's a long haul south through Cowley Canyon before you take road No. 147 and head east and intersect road No. 056 coming from Blacksmith Fork Canyon.

3. Blacksmith's Left-Hand Fork. Take the Left-Hand Fork Road (five miles up Blacksmith Fork Canyon). This is a good gravel road for about 12 miles. From there, stay on the much more rugged road No. 055 for about two miles, but the tricky part is to be sure and turn at Dip Hollow onto Road No. 056.

4. Hardware Ranch. The dirt road from Hardware Ranch, No. 054, heads north. It eventually intersects the road from Left-Hand Fork near Dip Hollow. It's about eight miles, one-way from the ranch, to the grave from here.

--An account of Old Eph's final night:

Killing of bear ended decadelong struggle ....

There are several accounts of Frank Clark's decadelong struggle to eliminate the bear that had killed countless of his sheep, but one of the shortest and best was told by Clark to forest ranger Owen Despain in 1959 and was published by reporter Chris Nielsen in the Deseret News:

"The bear called `Ephraim' was not seen until the summer of 1914 when he walked up to my pal, Sam Kemp, who was fully armed but was so taken by this great animal that he let him pass on," Clark said 31 years ago.

"Old Ephraim had a small pool where he would bath about every six days. (He would eat a sheep, perhaps two, first . . . so it came to my mind he could be trapped in that pool. So we started on him, but no success. Year after year, he would gently lift that trap out of that pool without setting it off.

"The spring of 1923 came and the trap was sprung but it did not catch Ephraim. Oh, no! He was suspicious. So he dug another pool and drained the old one into it. What do you think was in his mind?

"When I arrived, I was just a little discouraged, but I put the trap into the new pool, stirred the mud and let it settle good and thick. . . ." (Clark then returned to his camp for the night, about three-quarters of a mile downstream in Logan Canyon's Right Hand Fork.)

"But I was awakened by a strange sound upstream - an awful roar and scream, mingled pain and misery. It would ring around the hills, and between screams it seemed that everything was listening for the next one.

"I tried to go back to sleep but couldn't for some time, and then I thought it might be a horse down. They make an awful noise in their agony. So, I got up, put my shoes on and in my underwear went up the trail a block and stopped to listen. The roar was between me and the camp!

"What should I do? The canyon sides were covered with thick brush and that animal. No matches. I was already shaking with cold. There were only seven cartridges in the 25-35 (the small game rifle of that era) and steel balls. The best thing to do was to keep quiet and listen to that animal for the rest of the night. I had walked within 10 feet of him.

"Daylight at last and plenty mad so I went down. There he was, under some willows in a deep wash. I couldn't see him very good so I got a pole and tried to poke him out. He gave me the slip and went down to camp and got in some short willows. I got sight of a little piece of bear and shot into it.

"And now Ephraim rose all in his greatness, 1,100 pounds, 9-feet 11-inches, with a 14-foot log chain wound around his right forepaw and a 23-pound beartrap held up like a mate taking an oath, his back toward me.

"He turned and walked toward me, and when he was 10 feet away I poked out the gun and fired. He staggered back and came on. Shot again and he staggered back, but never off his hind feet. There was a 3-foot bank between me and him and the trail. Five bullets and he was still on his feet.

"Now something new. He turned half around and started to walk up the creek to where the trail crossed and came walking towards me on his hind legs, chain and trap held high above his head."

Clark broke cover and ran.

"I looked back, here comes Ephraim, and now, for the first time my dog showed up and Eph turned to protect his heels. I turned back and urged the dog on.

"The bear was badly hurt. Every time he breathed, blood squirted from his nostrils. So I got up close and fired my last shot into head or neck and down he went.

"I sat down and watched his spirit depart from that great body and it seemed to take a long time, but at last, he raised his head a mite, gasped, and was still.

"Was I happy? No, and if I had to do it over I wouldn't kill him. . . . I could see the suffering in his eyes as he tried to climb that bank."

Shaken, cold and hungry, Clark went to Sheep Creek to find Joe Brown at a nearby camp. The two men returned and skinned the bear. Since they were unable to move it - the hide alone weighed about 200 pounds - Clark burned the body in a fire that last three days and later returned to bury the skeleton.

Clark claimed to have killed 43 bears in his 34 years of sheepherding, but Ephraim was his last by choice.

AUTHOR'S NOTE: This 1990 story inspired the making of John Denver's last movie -- "Walking Thunder."

Photos by Lynn Arave.

-NOTE: The author, Lynn Arave, is available to speak to groups, clubs, classes or other organizations about Utah history at no charge. He can be contacted by email at: lynnarave@comcast.net

No comments:

Post a Comment