MOST FOLKS catch sight of the

House Mountains from the vaunted "loneliest highway in America," U.S.

50-6, as they approach Skull Rock Pass, either from Delta, 45 miles to the

east, or the Utah-Nevada state line to the west.

Their gaze might initially be attracted

to the glaring playa to the south that signifies, at this time of year, the bed

of Sevier Lake. After all, catching sight of a leftover puddle, a fleeting

mirage or some sorry case who's, on a lark, gone and gotten his pickup truck

stuck in the near-shore mud can break up a long stretch of driving.Then there's

that curious nick atop an elongated hump off to the north. Wondering about it

can be diverting, if only momentarily. For overall, the House Mountains, of

which this peak is a part, seem rather undistinguished. The desert range does

not loom from afar so much as sit there like a lump.

"It doesn't look like

there's anything to it," admits Lynn Fergus, outdoor recreation planner

for the Bureau of Land Management.

But as Fergus knows well - for this

is part of his "beat" - appearances can be deceiving.

This landscape makes up a

fascinating chunk of Utah's outback.

The alluvium fanning out from the

serrated peaks - Notch/Saw-tooth, Howell and Swasey most prominently -

underlies gravel roads that are kept up pretty well by Millard County crews.

"Often you can zip along as if on pavement," Bill Weir and Robert

Blake note in their "Utah Handbook," "but watch out for loose

gravel, large rocks, flash floods and deep ruts that sometimes appear on these

backcountry stretches."

The north side of Notch Peak.

The roads allow access to hidden

canyons, springs, stands of aged bristlecone pines, wildlife (including a herd

of wild horses), old mining claims and outcrops harboring trilobites and

primordial invertebrate life forms. They loop around the mountains, climb to

high vistas like the Pine Peak and Sinbad overlooks, and wiggle through Marjum

and Dome Canyon passes.

Scenic characteristics from other

Utah locales come to mind when you get up close: "Lion King" prows on

the eastern approach to Marjum Pass echo tilted buttes near Flaming Gorge;

narrow box canyons and pink cliffs have relatives in Canyonlands and Zion; the

high, green Amasa Valley surely belongs in another string of mountains

altogether.

The House Range is hard

wilderness country: dry, contorted - and often dramatically vertical. Camping

is primitive, and hiking can be challenging, with no markers to speak of. A

guidebook - or better yet, a guide - may be a good idea.

Nevertheless, more and more

people are discovering these surprisingly accessible mountains.

The final approach to the top of Notch Peak.

Notch Peak in particular, Fergus

says, is gaining a reputation.

David G. rhapsodizes: "It's

not heaven, but you can see it from here."

Carl B. takes in the view then

decides to "sit back, close my eyes and imagine Lake Bonneville filled to

the brim."

Notch Peak, the summit of

Sawtooth Mountain, has its own "mailbox," one of those familiar

general-issue tin versions embedded in an impressive rock cairn. According to a

notebook inscription found therein, the mailbox was first placed there by the

Wasatch Mountain Club in 1968. So shiny it looks nearly new, it is often

stuffed with notes left by hikers - Scout troops, people in pairs and small

groups - who reached the peak.

Notch seems to give just about

everyone a tingle of acrophobia.

"Wow! Dang," Erick,

Lisa and Sue succinctly exclaim.

"It gives me the heebie

jeebies," notes an unknown scribe.

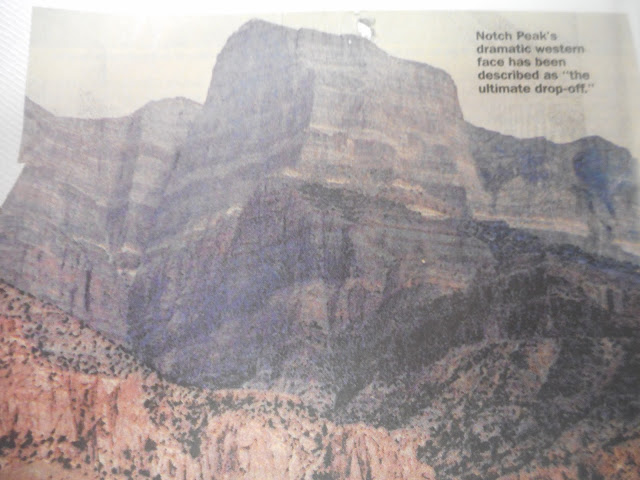

Sheer, steep, lofty, abrupt -

adjectives don't do this escarpment justice. John Hart, in his book

"Hiking the Great Basin," writes that a Notch Peak climb will refine

your use of the word "cliff." It is, he says, "the ultimate

drop-off."

A hike to the top begins at the

mouth of Sawtooth Canyon, on the mountain's southeast side. A shot-up sign

meant to direct motorists to nearby Miller Canyon (the placard on the main

unpaved road heading north says " 'er Canyon") sends adventurers

west; at a Y intersection, the road on the right heads to Miller, while the one

on the left bumps toward Sawtooth.

Sawtooth itself opens with

dramatic cliffs. The drainage leading toward the peak turns west then north.

The canyon becomes quite narrow, with brushy sides, fallen conifers and a

barely discernable trail. Finally hikers head up a ridge toward the peak.

Before they get there, though, the mountain suddenly breaks open and YIKES! A

massive cleft opens up, a yaw that certainly contributes to the notch visible

from scores of miles away. The mountain's limestone foundations swirl in a

sequence of sedimentary layers.

From the peak itself, Notch, at

9,655 feet above sea level, drops 5,053 vertical feet on its west side to the

bleak but beautiful sagebrush-and-alkali Tule Valley below.

That, as Fergus points out, is

nigh on a mile.

Then there's the view from the

top: a panorama of desert valleys and distant ranges. On a clear day there are

more sights to behold than you may have time to drink in.

"Scenic overdose," two

Provo hikers scribbled in a mailbox note.

"I hope you brought your

hang glider for an easy descent," wrote Matt and Kristen.

To the east and southeast are

Scipio Peak, the Sevier Dry Lake and the Pavant and Tushar mountains. To the

south are Utah's San Francisco and Wah Wah ranges. The Confusions are in the

immediate western foreground, with the Deep Creeks off to the northwest.

Several key peaks can be spotted beyond the Nevada state line - Mount Moriah

(elevation: 12,050 feet) and Wheeler Peak (13,061 feet) float far to the west

and southwest; Pilot Peak is to the extreme northwest.

And if you hate hiking?

From the northeast, a rugged

four-wheel track climbs into the spring-fed Amasa Valley (the locals pronounce

it Ama-seh, Fergus adds), past old mining equipment and a collapsed cabin to

the Pine Peak overlook. The view toward the Silver State is much the same,

without the summit's plunge but with the addition of some nice groves of aspen

and pinnacles and boulders of rusty granite.

Near the ridges are enticing

campsites, Fergus vouches. His wife loves to stargaze, so he brought her into

the area last summer.

"She said she couldn't find

the constellations - there were too many stars."

While Notch is gaining a name,

some long-time residents of the region are already somewhat famous.

That's "long-time" as

in since the Paleozoic, some 400 million years or so ago.

At the S & S Trading Post and

Neno's Rock Shop at the west end of Delta, Nina Higgs pulls out a handsome

book. There they are: portraits of Elrathia walcott and Ptychagnostus

richmondensis (walcott) - two of the 60 species of trilobites found in Utah's

House Mountains. Other pictures show creatures found today in such disparate

locales as Sweden and Newfoundland.

West-central Utah is famous among

rockhounds, Higgs notes. People from all over the world - but especially from

the Wasatch Front - visit to seek out topaz near Topaz Mountain to the north,

geodes and trilobites. Though long extinct, the latter, small bottom-feeding

bug-like animals, are preserved by the millions in Wheeler Formation shale.

The shale is exposed throughout

the area. On BLM land, visitors are allowed to chip away at the rock if they

want to find a trilobite or two. Collecting is legal, "as long as it's

invertebrate" - i.e., no dinosaur bones, which aren't in this vicinity

anyway - "and as long as it's not commercial," Fergus says. Technically,

then, any discoveries made are not to be for sale, "but it's really hard

to enforce; we just don't have the people to do it."

He takes his Blazer off the main

track toward gray-green hills. A winding jeep trail leads to a trilobite bed

that's semi-secret, though a trench and tons of chipped rock show it has been

visited frequently enough. A small pick in hand, within minutes he's revealed a

few trilobites: dark, tripartite, scarab-like fossils that look like they could

have been embedded there yesterday. Others are found by simply sorting through

the debris.

Various BLM and guide maps point

the way to such deposits, but few are specifically marked for would-be hounds.

On state parcels - the

"school lands" we've often heard about - commercial enterprises are

issued permits to excavate. At the U-Dig Fossils pit in Swasey Peak's Antelope

Springs drainage, for example, day-trippers are given directions and an

opportunity to uncover the ancient creatures.

"That's quite a hole, isn't

it," Fergus says. "They've been digging there a long time."

Other beings repose within the

rocks as well. Joe Bauman, who writes about science for the Deseret News, heads

occasionally to the House Range to look for reddish squiggles that may signify

sea life of almost unimaginable age. Trilobites pop out in 3-D; these

softer-bodied forms can be more chal-lenging to track down.

"I crack open rocks in hopes

of finding some new species of middle Cambrian invertebrate and because I enjoy

finding known varieties that are there," Bauman says. The middle Cambrian,

approximately 530 million years ago, was a time of great evolutionary

diversity.

Some discoveries seem downright

alien looking, he says, "like a critter that had seven eyes, paddles and a

trunk with a spiky grabber on the end of it." He's sent off several

examples to scientists.

For those "who don't want to

waste precious time getting there," Neno's offers full- and half-day

expeditions into the region, says Nina Higgs. The guides know where the

deposits are, provide the vehicle and tools, and bring along water, juices and

sanitary accessories.

Rockhounding, she says, is a

fast-growing hobby, and "something the whole family can do together."

The House Mountains have an open, outdoor appeal in themselves, and the fame of

the region's rocks is spreading.

"We see people from all over

the world, every walk of life, every nationality."

Like other dramatic Utah

settings, the House Mountains tend to make you wish you were a geologist, or at

least a better student of the subject.

Great Basin block faulting

created the mountains, tipped them up, stretched the valleys and cracked the

massive rocks to make narrow canyons. Erosion ate away at the peaks and filled

the gaps between then.

"The alluvium in these

valleys," Fergus says, "is something like 10,000 feet deep."

All this began some 18 million

years ago, according to Halka Chronic's book, "Roadside Geology of

Utah," when "stretching, thinning and breaking of the Earth's crust

began to create the Basin and Range mountains of western Utah, Arizona, Nevada

and California. . . . In Utah, most of the ranges are steeply faulted along

their western sides. Geologists soon likened this region to a pile of dominoes

all tilted in the same direction."

Another shaper of the landscape

was the Pleistocene's Lake Bonneville, the fresh-water ice-age ancestor of the

Great Salt Lake that covered vast stretches of territory. The shorelines remain

visible along the mountainsides and on hills that were once islands.

Yet another ingredient is molten

rock. At some point millions of years ago, magma seeped into the sedimentary

foundations of Notch Peak. The intrusion created a becoming red-tinged granite

visible in Miller Canyon, the Amasa Valley and on the western side of Notch.

And that granite, to prospectors of the 19th and 20th centuries, hinted at

precious metals like tungsten, silver and gold, which tend to migrate to the

edges of such rock when it is being formed.

And so there are mine claims in

the House Range. Some date back a century; others are on state lands: an old

wood-and-rock miner's cabin reposes near Sawtooth Canyon; sluice operations

continue intermittently in the gravels of Miller Canyon; the Amasa Valley is

sprinkled with mine heads and old equipment.

There's no indication anybody hit

a motherlode here, so you have to wonder: Did the mine operators get their

investment back?

"No, in a word," says

Fergus.

But still people have been drawn

to the House Range: There's evidence that Archaic Indians were here 10,000

years ago; the Paiutes and other tribes in more recent times; prospectors,

cattlemen and cowboys, sheepmen, freight haulers looking for a way through,

road builders - and a hermit. Bob Stinson, a World War I veteran, lived in

Marjum pass for years and years. In a side canyon he built a one-room home with

rock walls under a sheltering cliff.

"How would you like to spend

17 years of your life here?" Fergus wonders.

But rockhounding, hiking,

hunting, cave spelunking (Antelope Cave is open during part of the year), hobby

mining (as Fergus puts it) and other recreational pursuits seem to be part of

the future for these mountains and valleys.

That makes people like Fergus and

Higgs a bit apprehensive.

Old-time miners didn't tend to

clean up after themselves much, but modern recreationists can be just as

careless: You can't help but notice the accumulation of cans and bottles in

prime primitive camping spots. ATVs and four-wheel-drive vehicles can do

serious damage in such terrain.

"What you get out in this

area is someone will cut out into the brush and someone else will come along to

see where they went. Pretty soon you have a `road,' " says Fergus, one of

whose jobs is to keep an eye on three wilderness study areas in the vicinity.

Higgs, too, expresses concerns

about how people treat it, from traveling across the valleys to finding a place

to potty.

"In the past five years I've

seen it grow so fast. I'm not sad - I'm trying to make a living off it."

Yet, she adds, "People think

the desert is forever, but it is fragile."

-By Lynn

Arave and Ray Boren and originally published in the Deseret News, Aug. 24, 1997.

No comments:

Post a Comment